UC-Davis Genetic Diversity Study

We are excited to have partnered with the University of California at Davis, one of the top canine genetic research labs in the country, for our canine genetic diversity study!

A Simple Breakdown of the What and Why

THE REALLY REALLY SHORT VERSION:

If you don’t have a lot of time to read, here’s the quick one-page TLDR:

Genetic diversity helps prevent the undesirable effects of past inbreeding. Most purebred dogs have a lot of inbreeding behind them—not necessarily in their immediate pedigree, but from way back when their breeds were first created. If a breed never introduces any fresh blood, the effects of that inbreeding never go away. In fact, if a breed is not well-managed, things can get worse, which is why it’s rare these days to hear about a “healthy” breed of purebred dog. Some of the undesirable effects of inbreeding include more genetic disease, weaker immune systems, reproductive problems, and higher infant mortality.

The ISSA Shiloh Shepherd breeders all worked together to get a huge portion of our dogs into the UC-Davis study. We were seeing the beginning signs that our dogs were too related—more genetic disease popping up, more C-sections, and smaller litters. Our Shilohs were still pretty healthy—but it was taking careful management to stay that way.

Sure enough, the study proved what we suspected: ISSA Shiloh Shepherds have less genetic diversity than any other population of dogs in UC-Davis’s records. Our careful breed management had helped us to spread out the little diversity we did have. But now, we need to embrace this tool and move forward proactively.

A very small number of dogs were used to create our breed, and all of them were at least partially related. The UC-Davis study findings completely support this daunting fact. However, the study allowed us to locate the rare pockets of genes in our breed, so we can now work to save them. The idea is to keep our population healthier while we explore options to add fresh diversity (you can read about what we're working on here).

But does this sort of thing really work? Absolutely. Zookeepers working with endangered species have been using this type of information to preserve rare animal populations. Even livestock farmers have been using this technology to keep their animals healthy. So, we as dog breeders are a little late to the party…but with so many other programs like this having proven success, we have high hopes for the future!

That’s your short view. For more information, read on!

GENETIC DIVERSITY STUDY - OVERVIEW

First of all, what is it? There seems to be a bit of a misconception that completing and utilizing the diversity study will automatically fix things like hip dysplasia and other genetic diseases. This is not so! The burden of tracking and attempting to reduce genetic disease still sits firmly on each breeder and the registry.

Instead, the diversity study attempts to identify the negative effects of inbreeding--not just in a litter, but from the very beginning of the breed--so that they can be countered by a proactive breeding program keyed toward diversity. This can influence the incidence of genetic disorders in a positive manner, but it's not a magic bullet. It CAN significantly improve immune system and reproductive health.

THE ANTIDOTE TO INBREEDING

So, then, we can think of genetic diversity as the fix for too much inbreeding. Most purebred dogs were CREATED by inbreeding—it’s what established the “type” that defines them and gives them a different appearance and temperament compared to other breeds.

But once the stud book is closed and no fresh blood is allowed in, the effects of inbreeding done a hundred years ago are never escaped. If a breed is not well-managed, things can get worse. Even breeders who avoid inbreeding today are still working with stock from the same small pool of original dogs. Some more, some less, but they are all still suffering the effects of inbreeding.

For example, the ISSA Shiloh can be traced back to only twenty original dogs, and they were all at least partially related. No matter how many dogs we have in our gene pool today, the genes from those twenty dogs are ALL we have to work with.

So, what does it take to work toward breed-wide diversity? To make a real impact, this requires a group of breeders all working together to get dogs entered, who are then also committed to utilizing the results. ISSA’s breeders are committed as a group to utilizing this information to achieve a healthier Shiloh.

WHY DID WE DO IT THIS WAY?

As breeders, when the ISSA was created, we wanted to know exactly what we had to work with in our group of breeding animals. Most of us had taken population genetics classes via the Institute of Canine Biology, so we knew that a population of dogs could get in trouble if it lacked genetic diversity (if you have heard the terms "inbreeding depression" or "popular sire effect" then you know what we were worried about).

We did the diversity study, which sequences the DNA of our breeding dogs, to find out where we stood. We asked UC-Davis to separate our ISSA dogs from other Shilohs because we wanted to focus specifically on our own breeding population, and get some answers about the dogs we were moving forward with as our foundation stock.

IS THIS LIKE THE EMBARK DNA TEST?

Mostly, no. Embark does run a diversity analysis, but without a large cooperative effort, knowing your dog is diverse doesn't really help you to utilize that information. Embark's main focus is to run a large panel of DNA tests looking for a variety of specific traits. These include genes that can lead to genetic disease in some breeds, or genes that influence size, or the coat, or color. The UC-Davis test doesn't tell you any of that. Instead, it sequences a large variety of markers (called STR) that are in the gene regions that define differences between individuals.

But don't all of our genes do that? Actually, no. Did you know that only 0.5% (or less!) of your genetic code is what makes you different from any other human on the planet? Well, it's the same with dogs. All dogs, from the smallest Chihuahua to the largest Irish Wolfhound, have the same genetic makeup for the majority of their genes. Only a small portion is different and it is these markers that are run for things like determining paternity testing, or running forensics applications.

DLA AND STR

The UC-Davis test also separates out very useful groups of genes that have the potential for a lot of diversity called "DLA haplotypes". A haplotype is just a group of genes that are inherited together, in a block. The DLA haplotypes have been shown to have a strong influence on immune system health. Even in humans we know that a lot of genetic diseases are thought to have immune system factors; it appears to be the same in dogs.

The purpose of the UC-Davis testing is to determine how different our individual breeding dogs are, genetically; but it's also to see how much different material we potentially have at each location or gene. For example, some breeds possess a lot of different haplotypes in their DLA, while others have only a few possible variations. With STR, a really diverse group of dogs might have eight or nine possible alleles (gene variations) at one STR marker; a breed that's very interrelated might only have four.

Worse, there's something called "effective alleles" at each STR locus. What that means is, maybe you have 6 possible alleles in your breeding population at that marker, but most dogs are really related, so 80% of your gene pool only has the same two alleles and the other four are only in a relatively small population of dogs. The same applies to DLA; maybe your breed in total possesses eight Type I haplotypes, but the vast majority of dogs possess the same two or three.

Let’s look at the average number of alleles and effective STR alleles for a really diverse breed, the Havanese, and compare to our Shilohs.

Havanese:

Average number of alleles per locus: 8.88

Effective alleles per locus: 4.52

ISSA Shiloh Shepherds:

Average number of alleles per locus: 4.45

Effective alleles per locus: 2.63

Our Shilohs have only HALF the diversity of the Havanese when you put them side by side. Worse, almost half of the alleles that exist in our breed are held in only a small portion of Shilohs. Lack of diversity equals more effects from inbreeding, and rare alleles can be easily lost unless action is taken. Can you see why this could be a problem?

What the UC-Davis diversity study has done for us is to SHOW us where these rarer alleles or haplotypes are, so we can get those dogs used and produce offspring carry that diversity to spread it wider through our pool. The goal is to make sure we don't lose rare genetic material (which would essentially make our dogs more inbred--related--in the long run).

In summary, you want as much variety as you can get at each STR point, because it gives you "wiggle room"--it means you can make breeding decisions that match dogs who are as different as possible, hopefully lowering the chance of two "bad" genes matching up and producing issues. You want a lot of variety in your breeding population's DLA for healthier immune systems. Having a lot of variety in both of these things, and growing your population of breeding dogs, gives you a better chance to reduce genetic disorders when you combine it with a good disease-tracking initiative that encourages breeders to be honest about what they are producing.

THE RESULTS

After Phase One of UC-Davis testing, your study results are published on the UC-Davis web site.

You can read the full UC-Davis study results for our ISSA Shiloh Shepherds here.

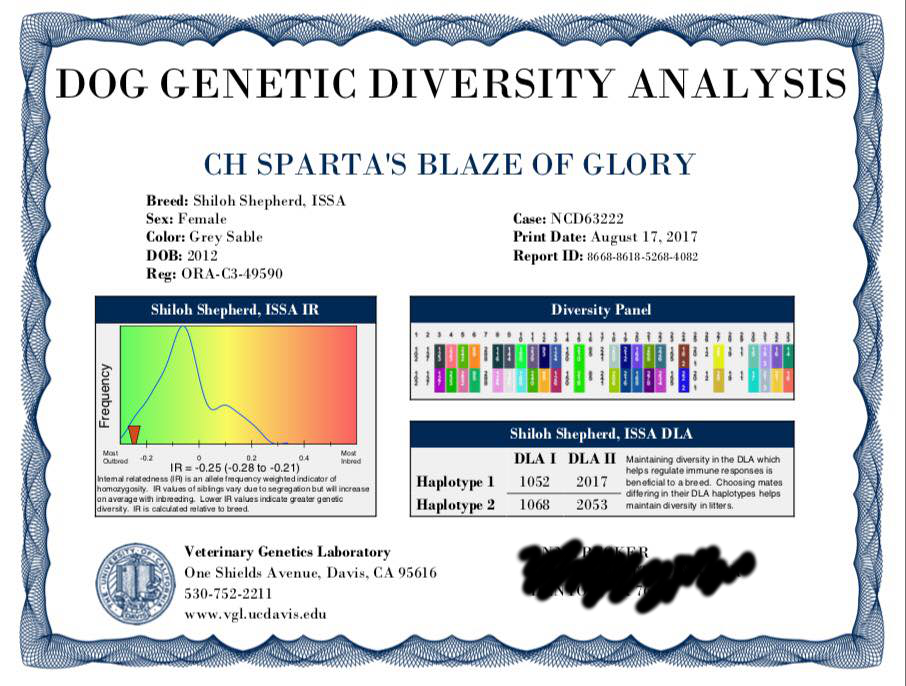

In addition, now that the base pool is established and the preliminary analysis complete, UC-Davis has mailed out the reports on each dog stating where it is on the scale from less diverse to more diverse, compared to a majority of the ISSA population. Here is an example from our ISSA Shilohs: CH Sparta's Blaze of Glory, aka Blazie.

How do we read Blazie's results? The box on the left tells us how diverse the genes within Blazie herself are. If she has two copies of the same marker at a gene, she is less diverse; if the two alleles are different, she is more diverse. In addition, if she has some rarer markers, she will end up further in the green. If you look for the red arrow in the box at the left, you can see that Blazie has a lot of diversity! The arrow is far to the left, in the green.

Looking at the right side of the report, we can see that this is probably because she has two different markers at a lot of her genes (the more different colors in the top right table, the more different markers are present). In addition, she possesses four different DLA haplotypes, with no duplicates. In order to see how many rare markers Blazie possesses, or to see if any of her DLA haplotypes are rare, we would need to consult her report, which is emailed out with the certificate, and then compare to the results detailed in the study itself.

It's important to note that two less diverse dogs can still produce very diverse pups if they carry different groupings of markers! Likewise, two diverse dogs can produce less diverse offspring if they carry a lot of the same sets of markers. So, it's more complex than it looks, and this report is only the beginning of the work. Now we enter phase two, utilizing this information.

In phase two, we continue to enter dogs; we attempt to utilize dogs who have rarer genetic material to make it more common, and we try to match dogs who are more genetically different so that we can hopefully steer the breed toward better health. We will also test new litters of pups, so that--in addition to good structure and stable temperament--we can choose the most genetically diverse pups to move forward in our breeding program.

THE FUTURE

All of these tactics allow us to preserve the diversity we already have. However...if you've read our page about why we believe we need to outcross, you know that this is only a small part of what we are planning. If we continue to breed only within the Shiloh Shepherd breed, it doesn't give us any more genetic "wiggle room." We can't all breed to the same dogs with the rare genes, and all it takes is a run of bad luck to lose animals with diversity that can't be replaced. One big thing that this study has confirmed for us is that we do need to outcross, to introduce fresh blood from an unrelated breed to help keep our dogs healthy.

So, if the only way to add new diversity into our gene pool is via outcrossing to a different breed, can we use this study to track the diversity in outcross pups, to keep the health benefits of outcrossing while carefully weaving the new strain into our breed? We believe we can. Starting with our first outcross, we'll be sending in his DNA to UC-Davis to see which alleles and gene groupings he possesses that our dogs don't. Then, when the first outcross pups arrive, we'll test all of them as well, to see how that diversity has come down. As we breed back to Shilohs to regain our appearance and temperament, we'll preserve as much of that diversity moving onward as we can.

If you read our Outcrossing Checklist, you know that we've set up rules for the Outcross pups from the first generation to ensure that all complete this testing with UC-Davis.

WHAT ABOUT MY DOG?

Have an ISSA dog that is a potential breeding animal and wondering if you can participate? You bet! The project remains open as we move forward, and anyone with an ISSA breeding dog that isn't already in the study can order a test under "Shiloh Shepherd, ISSA" and send in the swabs.

You can order the Canine Genetic Diversity test by creating an account on the UC-Davis page, and choosing Canine Genetic Diversity test--don't forget to choose "Shiloh Shepherd, ISSA" as your breed to make sure you are compared to the correct group of dogs! The cost of the test is $80.

They say it takes a village to raise a child. It also takes a dedicated community to develop a healthy breed. Thank you all so very much for your participation and support in this very important endeavor. We believe that this tool will assist our Shiloh shepherds to become one of the healthiest breeds in the world!

- Want to learn more about genetic diversity and our future plans? Click here to go to the ISSA's main Genetic Diversity page.

- You can go to our Breeders page here!

- How is a Shiloh Shepherd different from a German or King Shepherd? Read about it here.

- Read about the Shiloh Shepherd temperament here!